Gene therapy is one of the most exciting frontiers in medicine, moving beyond just treating symptoms to fixing diseases at their source: our own DNA. Think of your genetic code as the body’s core programming. When there’s a bug or a typo in that code, it can cause serious problems. Gene therapy is a way to go into that code and correct the error.

It’s less like a daily medication and more like a permanent software patch for your cells.

Getting to the Root of the Problem

At its heart, gene therapy is built on a straightforward idea: many diseases—like cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, and even some forms of inherited blindness—happen because of faulty genes. These “broken” genes might produce the wrong kind of protein, or no protein at all, leading to a cascade of health issues.

Traditional medicine often focuses on managing the downstream effects of these genetic errors. Gene therapy, on the other hand, aims to tackle the root cause head-on by delivering new or corrected genetic material directly into a person’s cells. The goal isn’t just to manage a condition, but to offer a lasting, and sometimes, one-time fix.

The Building Blocks of Gene Therapy

To really get what gene therapy is all about, it helps to break it down into its core moving parts. Every therapy, no matter how complex, relies on these four fundamental elements.

- The Problem: It all starts with a faulty gene. This is the single piece of genetic code that isn’t working correctly and is causing the disease.

- The Solution: Scientists create a therapeutic gene—a healthy, functional copy designed to replace or override the faulty one.

- The Delivery Vehicle: A carrier, called a vector, is needed to transport the therapeutic gene safely into the target cells. This is often a modified, harmless virus.

- The Goal: Once delivered, the new gene helps the cell produce the correct protein, restoring normal function and stopping the disease in its tracks.

The ultimate promise of gene therapy is to shift the paradigm from lifelong disease management to durable, single-treatment cures by correcting the fundamental genetic mistakes that drive illness.

This simple breakdown helps demystify the process. To make it even clearer, here’s a quick overview of these concepts.

Gene Therapy at a Glance

This table maps out the core components of gene therapy with a simple analogy to help you visualize how it all fits together.

| Concept | Simple Explanation | Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Faulty Gene | The source of the problem; a “typo” in the DNA code. | An incorrect instruction in a recipe book. |

| Therapeutic Gene | The solution; a corrected version of the gene. | The corrected instruction for the recipe. |

| Delivery Vector | The vehicle used to transport the therapeutic gene. | A courier delivering the corrected recipe page. |

| Restored Function | The desired outcome; cells work properly again. | The final dish is cooked correctly. |

By understanding these fundamentals, the complex science of rewriting our genetic code becomes much more approachable. With this foundation, we can now dig into the different ways scientists actually make these incredible cellular repairs happen.

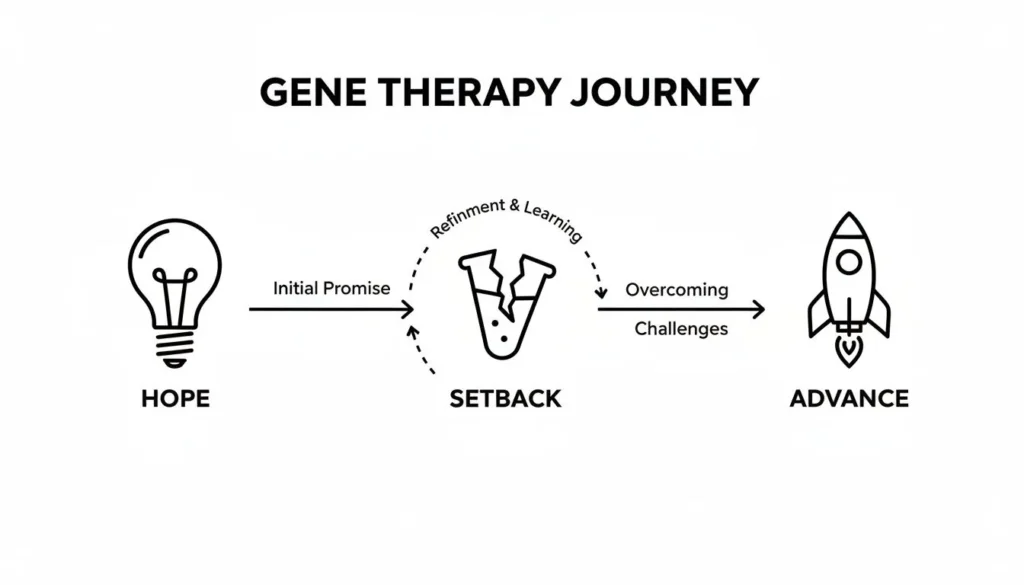

The Tumultuous Journey of Gene Therapy

The idea of rewriting our own genetic code is the stuff of science fiction. For decades, that’s exactly what it was—a distant dream for researchers trying to get at the root cause of disease. The road to making gene therapy a clinical reality has been a long and bumpy one, filled with incredible highs, devastating lows, and the sheer grit of the scientific community.

The theoretical gears started turning back in the 1960s and 70s. As scientists got a better handle on DNA and genetic disorders, they began asking a game-changing question: what if, instead of just treating symptoms, we could fix the faulty gene itself? That single question lit a fire that sparked decades of research, setting the stage for one of modern medicine’s boldest ambitions.

A Landmark Breakthrough and a Wave of Hope

Moving from theory to practice was a slow, painstaking process. But it all came to a head on September 14, 1990, when a four-year-old girl named Ashanthi DeSilva became the first person to be successfully treated with gene therapy. She had a severe immune disorder caused by one broken gene. Doctors took her own cells, engineered them to carry a working copy of that gene, and returned them to her body.

This first success wasn’t just a scientific milestone; it was a beacon of hope. It signaled that the era of genetic medicine might finally be dawning and that the answer to “what is gene therapy” was finally moving from the lab bench to the bedside.

That initial success unleashed a tidal wave of optimism. Scientists, doctors, and the public all started to imagine a future where we could systematically correct genetic diseases. The path forward, however, turned out to be far rockier than anyone could have guessed.

The Sobering Reality of Setbacks

The high hopes of the early 90s were tragically cut short. A series of high-profile failures exposed just how risky this powerful new technology was, forcing the entire field to slam on the brakes and rethink everything.

In 1999, the death of 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger, who suffered a massive immune reaction to the viral vector used in his treatment, sent shockwaves through the research world. A few years later, another trial in Europe that cured several children of an immune disorder had a terrible side effect: some of the patients later developed leukemia. You can see how these events shaped the field by exploring a detailed timeline of the history of gene therapies at Synthego.com.

These events brought two critical dangers into sharp focus:

- Immune Reactions: The body could launch a powerful, sometimes deadly, attack against the viral “delivery trucks” carrying the new genes.

- Off-Target Effects: The therapeutic gene could wedge itself into the wrong spot in our DNA, sometimes flipping the switch on a cancer-causing gene.

Rising from the Ashes with Safer Science

These tragedies were a harsh lesson, but they weren’t the end of the story. Far from it. They forced the entire field to regroup and become laser-focused on safety and precision. Researchers went back to the drawing board to engineer better, safer delivery vehicles, like adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). These newer vectors are much less likely to provoke the immune system or randomly splice themselves into dangerous parts of our genome.

This relentless focus on safety paved the way for the sophisticated and targeted therapies we have today. The tough lessons from the past led directly to better tools and a much deeper respect for the complexities of human genetics. It was this careful, measured progress that allowed gene therapy to re-emerge, built on a foundation of resilience and hard-won wisdom, as one of the most promising frontiers in medicine.

How Gene Therapy Actually Works

To really get what gene therapy is, we need to peek under the hood and see how it works inside the body. At its heart, the whole process boils down to two key parts: the therapeutic gene itself and a delivery system to get it where it needs to go.

Think of it as a microscopic special delivery service for your cells. The therapeutic gene is the “package”—a carefully designed bit of genetic material meant to fix a specific problem. The delivery vehicle, called a vector, is the courier. Its job is to safely transport that package into the right cells without getting lost or causing any trouble on the way.

This simple package-and-courier system is the foundation for all the incredibly precise work that follows.

The Three Main Strategies for Genetic Repair

Not all genetic problems are the same, so scientists need a few different tools in their toolkit. Most gene therapies use one of three main strategies, each with a very different goal.

- Gene Addition (or Replacement): This is the classic approach. When a gene is missing or just doesn’t work right, this strategy delivers a brand new, functional copy into the cell. The new gene doesn’t actually replace the faulty one; it just gets added to the cell’s command center, the nucleus. Once there, it can start producing the protein that was missing, bringing things back to normal.

- Gene Editing: This is a much more precise technique, almost like genetic surgery. Instead of just adding a new gene, gene editing aims to directly fix the original mistake. Using “molecular scissors” like the famous CRISPR-Cas9, scientists can snip the DNA at a specific spot, cut out the bad code, and paste in the correct sequence. It’s the biological version of finding a typo in a document and hitting “find and replace.”

- Gene Silencing: Sometimes the issue isn’t a missing protein, but a harmful one being churned out by a rogue gene. In these cases, the goal is simple: turn that troublemaker off. Gene silencing techniques introduce material that physically blocks the cell from reading the faulty gene’s instructions, effectively muting its harmful effects.

This journey from early hope to modern success was built on figuring out which of these strategies works best for which disease.

Delivering the Goods: In Vivo vs. Ex Vivo

Okay, so we have our genetic package and a plan for what it needs to do. Now for the most important part: how do we get it there? The delivery route is everything, and there are two main methods for administering gene therapy.

The choice between them comes down to one question: are the cells we need to fix easier to treat inside the body, or can we get better, safer results by working on them in a lab? This is the core difference between in vivo and ex vivo therapy.

Comparing In Vivo and Ex Vivo Gene Therapy

Let’s break down the two main delivery methods.

| Feature | In Vivo Therapy | Ex Vivo Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Process | The therapy is injected or infused directly into the patient’s body. | The patient’s cells are removed, treated in a lab, and then returned to the body. |

| Delivery | Vectors travel through the body to find and enter target cells on their own. | Vectors are used to modify the cells in a controlled laboratory setting. |

| Use Cases | Diseases affecting internal organs that can’t be removed, like the eyes, muscles, or liver. | Primarily for blood and immune system disorders (e.g., sickle cell disease, some cancers). |

| Pros | Simpler procedure for the patient; can reach tissues that are hard to access. | Highly controlled; ensures the right cells get the therapy; reduces risk of off-target effects. |

| Cons | Less control over where the vector goes; potential for immune reactions to the vector. | More complex and expensive; only suitable for cells that can be removed and returned. |

In vivo therapy, which means “in the living,” is just what it sounds like. The treatment is delivered straight into the patient, usually with an injection or an IV drip. The vector then has to navigate the body to find its target. This is the only option for treating diseases in places like the brain or heart.

Ex vivo therapy, meaning “outside the living body,” is a multi-step process. First, doctors take cells out of the patient—often blood stem cells from their bone marrow. These cells are sent to a lab, where the therapeutic gene is inserted. Finally, these newly engineered cells are infused back into the patient, ready to get to work.

While more complex, the ex vivo approach gives scientists incredible control, which is why it’s a game-changer for many blood disorders. Each route has its place, and choosing the right one is critical for success.

The Gene Editing Toolbox: From Blurry to High-Definition

To really get a handle on modern gene therapy, you have to look at the tools that make it all possible. Think of the earliest attempts at genetic therapy like using a sledgehammer for a delicate repair—powerful, sure, but not exactly precise. Scientists needed something far more refined, a toolkit that could operate on the scale of a single letter in our DNA.

The first real steps toward that kind of precision came with technologies called Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and TALENs. These were the original “molecular scalpels,” designed to slice DNA at specific spots. They were groundbreaking, proving that we could target and modify DNA, but they were also complex and a pain to engineer for each new job. They paved the way for a much more elegant solution.

CRISPR Enters the Scene

The true game-changer arrived with a tool that made gene editing faster, cheaper, and ridiculously more accurate: CRISPR-Cas9. While it’s often called “molecular scissors,” it’s more like a biological word processor with an incredibly precise search-and-replace function.

The system is built on two key parts:

- The Guide RNA: This is like a biological GPS coordinate, programmed to find a very specific sequence of DNA within the massive library of the human genome.

- The Cas9 Protein: This is the “scissors” part. It’s an enzyme that hitches a ride with the guide RNA and, once the right spot is found, makes a clean cut in the DNA.

By simply swapping out the guide RNA, scientists can direct these scissors to almost any gene they want to tweak.

CRISPR’s relative simplicity and incredible precision took gene editing from a highly specialized, labor-intensive process and turned it into a widely accessible tool. This single technology floored the accelerator on research, making treatments that were once purely theoretical a clinical reality.

This evolution of tools has been dramatic. We’ve moved from the somewhat clumsy gene additions of early therapies to the precise DNA rewriting made possible by CRISPR. After ZFNs and TALENs appeared in the 2000s, the adaptation of CRISPR from bacterial defense systems around 2012 completely changed the field. It’s what led directly to treatments like Casgevy, the first-ever CRISPR therapy approved in 2023 for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia, which comes with a price tag of $2.2 million. You can discover more about the history of these tools on The Gene Home.

From Rough Edits to High-Definition Surgery

Going from ZFNs and TALENs to CRISPR is like upgrading from a blurry, out-of-focus image to stunning high-definition. The older tools were clunky; CRISPR is programmable and efficient. This wasn’t just a small step forward—it fundamentally changed what scientists could even dream of attempting.

Take Casgevy, for example. The therapy works by taking a patient’s own blood stem cells, using CRISPR to edit a specific gene to kickstart the production of healthy hemoglobin, and then infusing those corrected cells back into the body. This kind of precise “DNA surgery” would have been nearly impossible, and certainly not scalable, with the earlier tech. This ever-improving toolbox is the engine that’s driving modern gene therapy, turning faulty genetic blueprints into treatable conditions.

Real-World Cures and Life-Changing Treatments

The science is fascinating, but the true measure of gene therapy is in the lives it saves and transforms. After decades of meticulous research, we’re finally seeing a wave of approved treatments that do more than just manage symptoms—they offer functional cures and give people a second chance at life.

These aren’t just lab concepts anymore. They are real-world solutions restoring sight to the blind, saving infants from fatal muscle-wasting diseases, and freeing patients from a lifetime of chronic pain. Each approval tells a story of how fixing a single genetic “typo” can completely rewrite a person’s future.

Luxturna: Restoring Sight One Gene at a Time

Imagine your world slowly fading to black. That’s the reality for people with a rare, inherited blindness caused by mutations in the RPE65 gene. This gene is the blueprint for a protein that’s absolutely vital for vision. Without it, the light-sensing cells in the retina simply die off over time.

Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec) tackles this problem head-on. It’s an in vivo gene therapy delivered directly into the eye, where it gets to work by:

- Delivering a Fix: A harmless, engineered virus (an AAV) acts as a tiny delivery truck, carrying a healthy copy of the RPE65 gene straight to the retinal cells.

- Restarting Production: Once inside, the new gene starts making the crucial protein that was missing.

- Turning the Lights Back On: This allows the photoreceptor cells to function properly again, dramatically improving a patient’s ability to see and navigate the world.

The impact is nothing short of profound. Instead of facing inevitable blindness, patients can experience a significant restoration of their sight. We’re talking about seeing stars for the first time, reading a book, or recognizing the faces of loved ones.

Zolgensma: A Lifeline for Infants with SMA

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a particularly cruel genetic disease. It’s caused by a faulty SMN1 gene, which stops the body from making a protein that motor neurons need to survive. In its most severe form, infants lose muscle control with shocking speed, eventually losing the ability to breathe. Most don’t live past their second birthday.

Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec) is a one-time infusion designed to stop this devastating progression in its tracks. The therapy delivers a working copy of the SMN1 gene throughout the body. This allows motor neurons to produce the vital SMN protein again, preserving muscle function and completely altering the course of the disease.

For families hit with an SMA diagnosis, Zolgensma is a game-changer. It gives their children the chance not just to survive, but to hit milestones like sitting up, crawling, and even walking—things once thought impossible.

Casgevy: The First CRISPR Cure for Blood Disorders

Sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia are inherited blood disorders that mean a lifetime of agonizing pain, organ damage, and endless medical care, including frequent blood transfusions. Both conditions stem from errors in the gene that produces hemoglobin, the protein that carries oxygen in our red blood cells.

Enter Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel), the very first approved therapy to use the revolutionary CRISPR gene-editing tool. It’s a sophisticated ex vivo treatment that works like this:

- Harvesting a Patient’s Cells: Doctors collect a patient’s own blood stem cells.

- Editing the DNA: In a lab, CRISPR technology is used to make a precise edit to a gene in those cells. This edit essentially flips a switch, turning back on the production of a healthy form of hemoglobin that our bodies normally only make before birth.

- Returning the Corrected Cells: The newly edited, super-powered cells are infused back into the patient.

This process enables the body to start producing its own healthy red blood cells, offering what is effectively a functional cure. The pace of progress has been staggering. Since the U.S. approved Luxturna in December 2017—which improved vision in 93% of patients—the field has exploded. Zolgensma, approved in 2019, cut mortality in infants with SMA by 79% at the two-year mark. Then, by 2023, the CRISPR-based Casgevy got the green light after a trial showed 27 out of 31 sickle cell patients were free from pain crises and no longer needed transfusions a year after treatment.

You can find more details on these and other treatments by exploring the history of approved gene therapies and their outcomes on Wikipedia.

Promise and Perils: The Future of Gene Therapy

Gene therapy is standing at a fascinating crossroads, bringing a vision of medicine that once felt like pure science fiction into the realm of possibility. The central promise here is profound: a shift away from a lifetime of managing chronic illness to the potential for durable, single-treatment cures. Imagine replacing a lifelong regimen of pills, infusions, or strict diets with a single intervention designed to correct the problem at its source—for good.

This is especially hopeful for what are known as monogenic diseases, conditions caused by a single faulty gene. For thousands of these disorders, from rare metabolic conditions to more common ones like cystic fibrosis, gene therapy offers the first real shot at a definitive fix, not just endless symptom management.

The Challenges Standing in the Way

As exciting as this is, the path from a promising therapy in a lab to a widely available treatment is paved with some serious scientific and practical hurdles. It’s a complex journey, and a few key challenges need to be ironed out.

- Immune System Reactions: The body is built to fight off anything it doesn’t recognize, and it can sometimes mistake a helpful viral vector for a hostile invader. A strong immune response can shut down the therapy before it has a chance to work or, in rare cases, trigger dangerous inflammation.

- Off-Target Effects: Gene editing tools like CRISPR are incredibly precise, but they aren’t perfect. There’s a small but very real risk that these “molecular scissors” could snip the wrong part of the DNA, leading to unintended and potentially harmful consequences.

- Long-Term Durability: For a one-and-done cure to truly deliver, its effects need to last a lifetime. Scientists are still tracking how long the benefits of current gene therapies will hold up and whether follow-up treatments might be necessary down the road.

The most significant issue seen with some gene therapies involves liver toxicity. As the body’s natural filter, the liver can become overstimulated while processing the viral vectors, a risk that requires careful patient monitoring and ongoing research into safer delivery methods.

Navigating Complex Ethical and Societal Questions

Beyond the lab, gene therapy forces us to wrestle with deep ethical and societal questions that have no easy answers. We’re talking about the very core of what it means to alter our biological blueprint and how to ensure these powerful new medicines benefit everyone, not just a select few.

Perhaps the most immediate barrier is cost and access. When a single treatment like Zolgensma comes with a $2.1 million price tag, the question of who can afford a cure becomes unavoidable. This creates a real risk of a two-tiered system where life-changing medicine is reserved for the wealthy, deepening the health disparities that already exist.

Then there’s the critical ethical line between somatic and germline gene therapy. Somatic therapy affects only the individual patient. Germline editing, on the other hand, would involve making changes to reproductive cells (sperm or eggs), which means those alterations would be passed down to all future generations. While not currently practiced in humans, the possibility alone raises huge questions about unforeseen long-term effects and the ethics of permanently altering the human gene pool.

The future of gene therapy hinges on our ability to navigate these issues thoughtfully. It requires a delicate balancing act—pushing the boundaries of science to cure devastating diseases while building strong ethical guardrails to ensure this powerful technology is used responsibly, safely, and equitably. The journey is complex, but the potential to alleviate so much human suffering makes it a path we have to pursue with both ambition and caution.

Common Questions About Gene Therapy

As gene therapy moves from the lab to the clinic, it naturally brings up a lot of questions. Let’s tackle some of the most common ones about safety, cost, accessibility, and the specific terms you’ll hear in this field.

Is Gene Therapy Safe?

Today’s gene therapies are worlds away from the earliest experiments in terms of safety. Big improvements in vector technology, especially the switch to adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), have dramatically lowered the risk of dangerous immune responses or the new gene ending up in the wrong spot.

That said, no medical treatment is ever 100% risk-free. There’s still a chance of the body having an unwanted immune reaction or “off-target” effects where a gene editing tool makes a change in the wrong place. To manage this, agencies like the FDA in the U.S. and the EMA in Europe have an incredibly strict testing and approval process. A therapy only gets the green light if its benefits are proven to far outweigh its known risks for a particular condition.

How Much Does Gene Therapy Cost?

There’s no sugarcoating it: the price tag for gene therapy is astronomical right now. We’re talking hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars for what is often a one-time treatment.

A couple of real-world examples: Zolgensma, for spinal muscular atrophy, runs about $2.1 million. Casgevy, a treatment for sickle cell disease, is priced at $2.2 million.

These eye-watering costs come from the massive investment poured into research, development, and incredibly complex manufacturing. The price also reflects the long-term value of a potential cure compared to a lifetime of managing a chronic illness. Still, cost is a huge hurdle for patients, insurance companies, and healthcare systems, and it’s a problem the field is actively trying to solve.

Can It Cure All Genetic Diseases?

Not yet. Gene therapy isn’t a silver bullet for every genetic condition.

Its biggest wins have been in monogenic diseases—those caused by a single faulty gene. Think of conditions like sickle cell disease or cystic fibrosis, where there’s a clear, singular target.

Things get much trickier with polygenic diseases like heart disease or diabetes. These conditions are caused by a complex mix of many different genes and environmental factors, making them far more difficult to treat with a single genetic fix. While researchers are definitely exploring this, the focus for now remains on single-gene disorders where the path from gene to disease is straightforward.

Think of it this way: Gene therapy is the overall strategy of using genes to treat a disease. Gene editing, like CRISPR, is one of the most advanced tools used in that strategy. So, all gene editing is a form of gene therapy, but not all gene therapy uses gene editing.

For instance, many of the earlier gene therapies relied on gene addition. This approach simply delivers a working copy of a gene into a cell without altering the faulty one that’s already there. Gene editing, on the other hand, allows scientists to go in and make precise changes directly to the existing DNA, like correcting a typo right in the genetic code. This shows just how much more precise genetic medicine is becoming.

At maxijournal.com, we bring you clear, accessible writing on the science and technology shaping our world. For more insights at the intersection of health, tech, and culture, explore our latest articles at https://maxijournal.com.