Writing a research paper often feels like trying to climb a mountain. You see the massive peak ahead and the first step seems impossible. The secret isn’t to just start climbing, but to break the entire journey into smaller, manageable trails. It’s a structured process: choose a focused topic, dive deep into the literature, build your argument logically (the IMRAD format is your best friend here), and then revise with a critical eye.

This approach turns that overwhelming feeling into a clear, step-by-step plan.

From Blank Page to Action Plan

Every great paper starts with an intimidatingly blank page. The initial phase isn’t about writing brilliant sentences; it’s about building a solid foundation. So many writers get stuck right here, paralyzed by the sheer scope of the project. But if you get this pre-writing stage right, you create a roadmap that will guide you through the entire process. Honestly, this is probably the most critical part—the choices you make now will echo through every draft.

The journey doesn’t start with writing; it starts with thinking. You need a topic that you actually find interesting and that has real academic weight. If you’re passionate about the subject, it’ll be a lot easier to get through the long hours of research and writing that lie ahead.

Finding Your Research Focus

The first real challenge is getting from a broad area of interest to a specific, answerable research question. A topic like “climate change” is a non-starter—it’s just too big for one paper. You have to narrow it down.

For example, instead of “climate change,” you might focus on “the impact of regenerative agriculture on soil carbon sequestration in the American Midwest.” See the difference? It’s specific, it’s measurable, and it has a clear scope.

To find your focus, ask yourself these questions:

- Where are the gaps? What questions haven’t been answered in the existing research? What ongoing debates could you contribute to?

- Is this actually doable? Do you have access to the data, tools, and resources you need to tackle this question? A brilliant idea is useless if you can’t execute it.

- Does it matter? Will the answer to your question add a meaningful piece to the puzzle in your field?

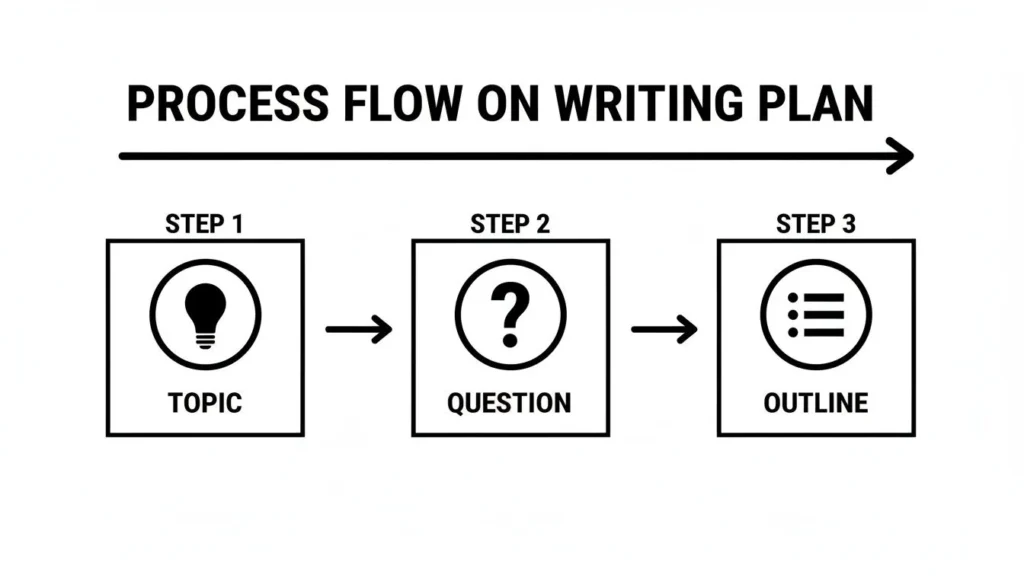

This flow chart nails the process of going from a general idea to a working outline.

As you can see, a powerful research question is the bridge that connects a vague interest to a concrete plan of attack.

From Question to Outline

Once you’ve nailed down a sharp research question, the next move is to sketch out a preliminary outline. This isn’t a rigid contract; think of it as a flexible skeleton for your paper. It’s like creating your table of contents before you start writing.

Map out your main sections: Introduction, Literature Review, Methodology, Results, and Discussion. This simple structure gives you direction and helps you organize your thoughts and your research from the get-go.

And the demand for good research has never been higher. Global research output shot up from 1.8 million articles in 2008 to 2.6 million by 2018, growing at about 4% a year. The landscape is competitive, but it also means a well-planned paper has a real chance to make an impact. You can read the full research on publishing trends to see the data for yourself.

The secret to getting ahead is getting started. The secret of getting started is breaking your complex overwhelming tasks into small manageable tasks, and starting on the first one. – Mark Twain

That quote is especially true for writing a research paper. When you break down the process, you transform a massive project into a series of achievable goals.

To help you get started, here’s a checklist that covers the essential pre-writing tasks. It’s designed to ensure you build a strong foundation before you even think about writing your first full paragraph.

Research Paper Planning Checklist

| Task | Key Objective | Success Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Brainstorm Broad Topics | Identify 3-5 general areas of personal and academic interest. | Don’t self-censor. Let ideas flow freely, even if they seem too big at first. |

| Conduct Preliminary Reading | Get a feel for the current conversation in your chosen areas. | Scan recent review articles or special journal issues to quickly understand the state of the field. |

| Identify a Research Gap | Pinpoint a specific, unanswered question or an underexplored niche. | Look for phrases like “further research is needed” or “the limitations of this study suggest…” |

| Formulate a Research Question | Craft a clear, focused, and arguable question that will guide your entire paper. | Your question should be specific enough to be answered within the scope of a single paper. |

| Assess Feasibility | Confirm you have access to the necessary data, tools, and expertise. | Be realistic. A great question you can’t answer is a dead end. |

| Create a Working Outline | Draft a basic structure (IMRAD) with bullet points for key arguments/data in each section. | This isn’t set in stone. Use it as a dynamic roadmap that can change as you write. |

| Set a Realistic Timeline | Allocate specific blocks of time for research, drafting, revision, and feedback. | Work backward from your final deadline and build in buffer time for unexpected delays. |

Using this checklist will help you move from that intimidating blank page to a concrete action plan, setting you up for a much smoother writing process.

Conducting a Literature Review That Works for You

Let’s get one thing straight: a literature review isn’t a book report. It’s not about stringing together a bunch of summaries. Think of it more like walking into a party that’s been going on for a while. You need to listen in on the conversations, figure out who’s arguing with whom, and find a spot to add your own two cents.

Your real goal here is to map out the existing territory of your topic. You’re doing detective work—looking for common themes, ongoing debates, and, most importantly, the gaps. Where did the previous research stop short? What questions are still unanswered? That’s where your work begins.

Strategic Searching for Sources

Jumping into a database like Google Scholar, Scopus, or Web of Science without a plan is a recipe for disaster. You’ll be buried under thousands of papers in minutes. You need a strategy.

Start with broad keywords, then get specific. For instance, you might begin with “renewable energy policy.” After skimming a few abstracts, you’ll find more precise terms, narrowing your search to something like “grid integration challenges for solar power in Europe.” That’s how you find the real gems.

Here are a few tricks I’ve learned over the years to search smarter, not harder:

- Follow the Citations: Found a killer paper that’s spot-on? Mine its reference list. This “backward searching” shows you the foundational work that shaped the field.

- See Who Cited It: Use your database’s “cited by” feature. This “forward searching” reveals how the conversation has evolved and who is building on that foundational work right now.

- Master the Filters: Don’t just type and hit enter. Filter by publication date to see the latest findings, by a specific author to follow a key researcher’s work, or by journal to stick to the most reputable sources.

Synthesizing Information Without Drowning in Detail

Okay, you’ve gathered a pile of papers. Now what? Reading every single word is a huge waste of time. You need to read with a purpose and have a system for organizing what you find.

This is where a literature review matrix becomes your best friend. It’s a simple spreadsheet where you track the essentials of each source. It’s the difference between collecting a pile of bricks and having a blueprint for a house. The matrix helps you see the connections and spot the patterns at a glance.

A literature review is a critical and in-depth evaluation of previous research. It is a summary and synopsis of a particular area of research, allowing anybody reading the paper to establish why you are pursuing this particular research program.

With a good matrix, you’re not just taking notes; you’re actively analyzing as you go. It transforms a passive reading list into a powerful tool for building your argument.

Creating Your Literature Review Matrix

Your matrix can be as simple or complex as you need, but here are the columns I’ve found most useful.

| Column | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Citation | Full bibliographic information so you don’t have to hunt for it later. | Smith, J. (2022). Advanced Widget Theory. Academic Press. |

| Main Argument | The paper’s core thesis, boiled down to one sentence. | Argues that widget efficiency is directly tied to gear-to-cog ratios. |

| Methodology | How the authors did their research. Was it quantitative? Qualitative? | Quantitative analysis of 500 widget performance tests. |

| Key Findings | The most critical results or conclusions. What did they actually discover? | A 2:1 gear-to-cog ratio increases efficiency by 15%. |

| Gaps/Limitations | What the authors admit they didn’t cover or where their study fell short. | Study only included widgets from a single manufacturer. |

| Your Critique | Your own take on the study’s strengths and weaknesses. | Strong data, but the limited sample size impacts generalizability. |

| Connections | How this paper speaks to others you’ve read. | Contradicts Jones (2021) but supports Chen (2019). |

This system does more than just save you from rereading papers. That “Gaps/Limitations” column is gold. When you start seeing patterns in what hasn’t been done, you’ve found your research gap.

This is how a literature review becomes the solid foundation of your paper. It’s not a chore to get through; it’s the process of proving that your research question is important and necessary.

Structuring Your Paper for Clarity and Impact

So, you’ve wrestled with the literature and have your data in hand. Now what? It’s time to build the framework that will hold it all together. Think of it this way: even the most groundbreaking research will fall flat if it’s presented as a jumbled mess of ideas. A solid structure isn’t just about following rules; it’s about making your work persuasive, logical, and easy for your reader to follow.

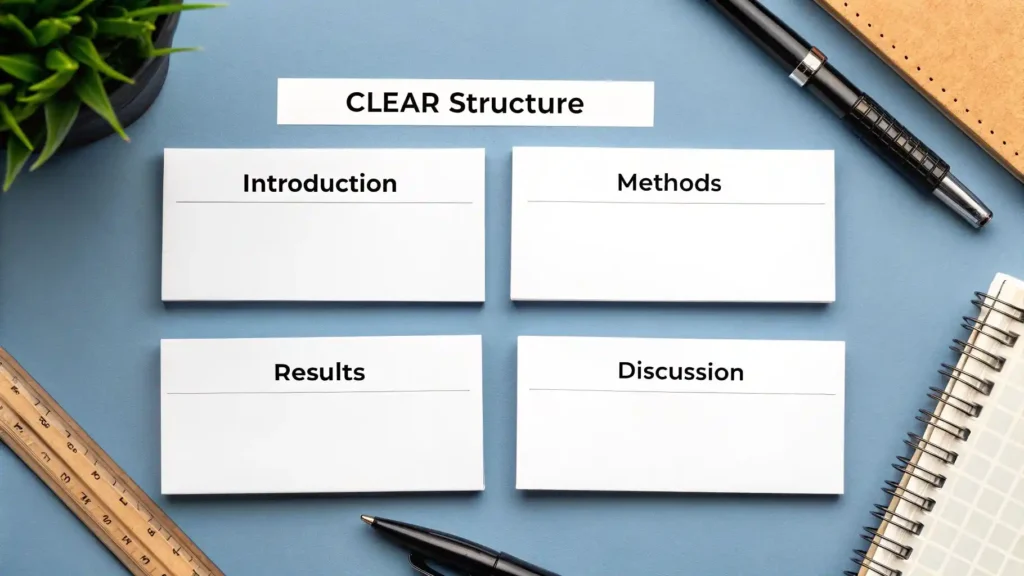

Across most scientific fields, the gold standard for this is the IMRAD format. It’s not a stuffy tradition—it’s a powerful storytelling tool that works because it mirrors the process of scientific inquiry itself.

IMRAD stands for Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. Each section tackles a critical question, creating a natural narrative that guides your reader: Why did you start? What did you do? What did you find? And what does it all mean?

To help you get a handle on this, here’s a quick breakdown of the IMRAD structure.

The IMRAD format provides a logical flow, guiding the reader from the broad problem to your specific findings and back out to the wider implications of your work.

| Section | Core Purpose | Essential Content to Include |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Establish the “why” | Background context, the specific gap in existing research, your clear research question or hypothesis. |

| Methods | Explain the “how” | Detailed description of participants, materials, step-by-step procedures, and data analysis techniques. |

| Results | Present the “what” | Objective reporting of your findings using text, tables, and figures. No interpretation here! |

| Discussion | Explain the “so what” | Interpretation of results, comparison to other studies, acknowledgment of limitations, and suggestions for future research. |

Let’s dive a bit deeper into what makes each of these sections tick.

The Introduction: Answering Why Your Research Matters

Your introduction is your handshake, your elevator pitch. Its job is to grab the reader, set the scene, and make a compelling case for why your research even needed to be done. You’re not just giving background; you’re identifying a problem.

A great way to think about it is like a funnel. You start broad and get progressively more specific.

- Set the Stage: Begin with the big picture. What’s the current state of knowledge in your field?

- Pinpoint the Problem: Next, you narrow your focus to the specific gap. What’s missing? What’s unresolved? This is the justification for your entire paper.

- State Your Mission: Finally, you present your research question or hypothesis as the direct answer to that gap. This is your thesis, the North Star for everything that follows.

A strong introduction doesn’t just present a topic; it presents a problem. It convinces the reader that a gap in our understanding exists and that your research is the necessary next step to filling it.

Get this right, and you’ve earned your reader’s attention.

The Methods: Describing How You Conducted the Research

This is the nuts-and-bolts section of your paper. Here, you lay out exactly what you did with enough precision that another researcher could, in theory, replicate your study. Transparency and meticulous detail are non-negotiable.

Think of it as a technical manual. Keep it objective and descriptive, and save all interpretation for later. The sole focus is on the “how.”

You’ll typically need to cover:

- Participants or Subjects: Who or what did you study? Describe your sample, how you chose it, and its size.

- Materials and Instruments: What specific equipment, surveys, or software did you use? Name names (and models, if it matters).

- Procedure: Walk the reader through your process step-by-step. What happened, and in what order?

- Data Analysis: How did you make sense of the data? Specify the statistical tests or analytical frameworks you applied.

You’re essentially writing a recipe. Clear, repeatable instructions are the bedrock of scientific credibility.

The Results: Presenting What You Found

It’s showtime. This is where you report your findings—just the facts, without any spin or interpretation. Since this section can get dense with data, clarity is your top priority.

Use a mix of text, tables, and figures to make your data as easy to digest as possible. Your text should act as a tour guide, highlighting the main takeaways and pointing to the visuals for the gritty details. For instance, you might state, “We found that Group A’s scores improved significantly more than Group B’s (a 15% difference on average), as shown in Table 1.”

Visuals are your best friend here:

- Tables are perfect for presenting precise numerical data in an organized way.

- Figures (like graphs and charts) excel at showing trends, relationships, and patterns at a glance.

Remember, the Results section answers the question, “What did you find?” The “So what?” comes next.

The Discussion: Interpreting Your Findings

This is where you bring it all home. The Discussion section is your chance to explain what your results mean in the grand scheme of things. You started by funneling down from a broad topic; now, you broaden back out, connecting your specific findings to the wider field.

A strong Discussion section will:

- Interpret the Results: Go beyond the numbers. What’s the story they tell? Directly answer the research question you posed in the introduction.

- Connect to the Literature: How do your findings stack up against previous studies? Do they confirm, contradict, or add a new wrinkle to existing knowledge?

- Acknowledge Limitations: No study is flawless. Being upfront about your research’s limitations and how they might have influenced the outcome actually builds your credibility.

- Point the Way Forward: Based on what you learned, what’s the next logical step? What new questions did your study raise?

This is your final opportunity to drive home the importance of your work. You’re closing the loop and showing exactly how you’ve added a valuable new piece to the puzzle.

Writing with Authority and Citing with Integrity

When you sit down to write, you’re doing two things at once: making an argument and proving it has merit. Strong academic writing is a dance between clarity and credibility. Your voice needs to be professional and persuasive, but every claim has to be anchored in solid, ethical scholarship. This is what separates a decent report from a research paper that gets taken seriously.

Writing with authority isn’t about using big words. It’s about communicating your ideas with a quiet confidence that comes from precision. You’re building a logical case, step-by-step, that’s easy for your reader to follow. Every sentence should pull its weight.

Crafting a Clear Academic Tone

A consistent academic tone is essential, but most people get this wrong. It doesn’t mean sounding stiff, formal, or overly complicated. Often, it’s the exact opposite.

Your number one goal is clarity. Here’s a good rule of thumb: if an expert from a different department can’t grasp your core argument, you haven’t explained it well enough. Think of your writing as a bridge between your niche expertise and the wider academic world.

A few practical tips to sharpen your tone:

- Embrace the Active Voice: “We analyzed the data” is direct and powerful. “The data was analyzed by us” is passive and clunky. Stick with the active voice whenever you can.

- Be Specific and Concise: Vague words like “interesting” or “significant” are red flags. Instead of telling me something is significant, show me how it’s significant. Quantify it. Explain the impact.

- Define Your Lingo: If you must use specialized jargon, define it clearly the first time you use it. Never assume your reader knows the exact same vocabulary you do.

This kind of precision is what makes your writing feel authoritative. You’re not just sharing thoughts; you’re presenting a carefully built argument.

Upholding Academic Integrity Through Citation

In research, credibility is everything. You earn it through meticulous, honest citation. Every idea you borrow, every piece of data you reference, and every theory you build on must be credited to the original author. This isn’t just about avoiding trouble—it’s about showing respect for the scholarly conversation you want to join.

Good citation does two things: it lets readers trace your intellectual footsteps, and it protects you from plagiarism, which is academic kryptonite.

The need for scholarly integrity has never been more critical. In 2023, the scientific community saw over 10,000 research papers retracted. That’s a new, and frankly alarming, record that points to a crisis in publishing. Digging into the data reveals the problem is worse in some places than others, sparking global concern over research ethics. You can read more about these academic publishing trends and challenges if you’re curious.

Citing your sources is the academic equivalent of showing your work in math class. It proves you did the homework, validates your answer, and lets others learn from your method.

Getting this right starts with understanding the major citation styles.

Navigating Major Citation Styles

While there are tons of citation styles out there, most fields lean on one of three big ones. Your professor, or the journal you’re submitting to, will tell you exactly which one to use.

- APA (American Psychological Association): The go-to for social sciences, education, and psychology. APA puts a big emphasis on the publication date, since timeliness is key in these fields.

- MLA (Modern Language Association): You’ll find this style all over the humanities—literature, arts, and philosophy. MLA focuses more on the author and often uses page numbers in the in-text citations.

- Chicago (Turabian Style): A really flexible style used across many disciplines, especially history. It gives you two options: a notes-and-bibliography system (footnotes or endnotes) or a simpler author-date system.

Trying to manage all this by hand is a recipe for frustration and mistakes. This is where reference management software becomes a non-negotiable tool for anyone serious about how to write a research paper efficiently.

Seriously, tools like Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote will save you dozens of hours. They let you:

- Build a searchable library of all your sources.

- Generate in-text citations and bibliographies with one click.

- Instantly switch between citation styles (a lifesaver if a journal rejects your paper and you need to reformat for a new one).

Spend a couple of hours learning one of these programs. It’s one of the smartest investments you can make. It frees you up to focus on the real work: building that clear, credible, and authoritative argument.

Getting It Ready: Revision, Submission, and Peer Review

Finishing that first draft feels incredible, a huge milestone. But the real work of shaping your research paper into a publishable piece is just beginning. Now you shift from creator to critic.

This is the refinement stage. It’s less about those big, breakthrough ideas and more about a sharp eye for detail. You’re stepping back, getting other people to weigh in, and learning to navigate the sometimes-tricky waters of academic publishing. Think of it this way: your first draft is the raw sculpture. Now it’s time to polish the stone until it shines.

The Fine Art of Self-Editing

Before your manuscript ever sees a reviewer’s inbox, you need to be its toughest editor. This is harder than it sounds. You’re so close to the work that you can’t always see its flaws. You know what you intended to write, making it easy to skim past clumsy phrasing or gaps in logic.

First things first: step away. Seriously. Put the draft aside for a few days, maybe even a week. When you come back to it, you’ll have fresh eyes, and all those little errors and awkward sentences you were blind to before will suddenly pop out.

Once you’re ready to dive back in, try a few battle-tested revision strategies:

- Read it out loud. This is a classic for a reason. It forces you to slow down and physically hear the rhythm of your sentences. You’ll catch clunky phrases and typos your eyes would otherwise skip right over.

- Do focused read-throughs. Don’t try to fix everything at once. Read it through once just for the flow of your argument. Then, do another pass for clarity and word choice. A third for grammar and punctuation. A final, painstaking pass just for typos.

- Print it out. Staring at the same screen for weeks on end can trick your brain. A physical copy changes the entire experience and helps you spot mistakes that were invisible on your monitor.

The point of revision isn’t just about correcting errors. It’s a deep conversation with your own work, a process of discovering the clearest, most powerful way to present your argument.

By being disciplined here, you ensure that when you finally ask for feedback, your peers and supervisors can focus on the strength of your ideas, not on distracting surface-level mistakes.

Submission and Surviving Peer Review

Once you’ve polished your manuscript until you can’t stand to look at it anymore, it’s time to find it a home. This means picking a target journal and getting it ready for submission.

Every journal has its own “Author Guidelines,” and you must follow them perfectly. This isn’t optional. They dictate everything from the citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago) and word count to how you need to format your tables and figures. Ignoring these is a fast track to a rejection letter before anyone even reads your paper.

You’ll also need a sharp, concise cover letter. This is your personal pitch to the editor. In just a few paragraphs, you need to sell your work: What’s your research question? What are your key findings? And, most importantly, why is this paper a perfect fit for this specific journal and its readers?

After you hit submit, your paper enters the peer review process. This is the cornerstone of academic publishing. A few anonymous experts in your field will read your work and provide a critique. Feedback can range from minor suggestions for clarification to a daunting “revise and resubmit” decision, which may require significant new work.

The key is to treat this feedback as a gift, not an attack. Stay professional. Create a document where you respond to every single one of the reviewer’s comments, point by point. Explain how you’ve addressed their concerns in the revised draft or, if you disagree, provide a thoughtful and respectful justification for why you didn’t make a particular change.

It’s also worth noting how much technology is changing this landscape. The days of pure manual editing are fading as more tech-mediated tools, from advanced grammar checkers to AI-driven feedback systems, become part of the process. While these tools can be helpful, the core principles of clear writing and rigorous peer review remain the bedrock of academic integrity. For those interested, you can read more about recent shifts in academic writing practices to see how the field is evolving.

Common Questions About Writing Research Papers

As you dive into the research process, you’re bound to run into a few common questions. It happens to everyone, from first-year undergraduates to seasoned academics. Below, I’ve tackled some of the most frequent sticking points to give you clear, practical answers.

How Long Should My Research Paper Be?

This is the classic question, but there’s no single magic number. The length is dictated entirely by the assignment guidelines or the journal’s submission requirements.

A typical undergraduate paper might land in the 5-7 page range, while a more in-depth graduate seminar paper could easily be 15-20 pages. If you’re aiming for a scientific journal, the sweet spot is often between 4,000-8,000 words.

Bottom line: always check the instructions first. If there are none, focus on being thorough without being wordy. Your job is to cover the topic comprehensively, not to fill pages with fluff.

What Is an Abstract and When Do I Write It?

Think of the abstract as the elevator pitch for your research. It’s a dense, powerful summary of your entire paper—usually around 150-250 words—that lays out your core question, methods, key findings, and main takeaways. It’s what convinces someone to either read your full paper or move on.

Here’s the most important tip: write the abstract last. It’s tempting to tackle it first, but you can’t summarize a paper that isn’t finished. Once your arguments are polished and your conclusions are set, you can distill the essence of your work into a sharp, accurate abstract.

An abstract is the most important single paragraph in your article. It gives readers a quick overview of your entire study, convincing them to either keep reading or move on.

How Many Sources Are Enough?

The real answer is “as many as it takes to make your case convincingly.” This is a classic case of quality over quantity. Ten highly relevant, peer-reviewed articles are infinitely more valuable than thirty sources that are only tangentially related to your topic.

A good rule of thumb is to make sure you’ve covered the foundational literature in your field and the most important recent studies. You’ll know you’re on the right track when you start seeing the same authors and papers cited over and over again. For most undergraduate papers, 8-12 quality sources is a great target.

What Is the Difference Between a Thesis and a Hypothesis?

These two terms get mixed up all the time, but they play very different roles.

A hypothesis is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to find. It’s the cornerstone of scientific and quantitative studies. For example: “Increased screen time will be negatively correlated with sleep quality in adolescents.”

A thesis statement, on the other hand, is the central argument or claim you’re going to prove. It’s common in the humanities and qualitative research. For instance: “Through its use of symbolism, The Great Gatsby critiques the illusion of the American Dream.”

One is a prediction you test with data; the other is an argument you support with evidence.

How Do I Handle Writer’s Block?

First, know that it’s completely normal. Staring at a blank page when you’re working on a big project is incredibly common. The worst thing you can do is try to force your way through it.

Instead, try to change your perspective and trick your brain into working again. Here are a few strategies that actually work:

- Switch sections. Stuck on the introduction? No problem. Jump over to your methods section or start organizing your results tables. Progress is progress.

- Create a reverse outline. Look at what you’ve already written and build an outline from that. Seeing the structure laid bare can often show you exactly what needs to come next.

- Just write freely. Set a timer for 15 minutes and just… write. Don’t worry about grammar, structure, or making sense. Just get words related to your topic on the page.

- Talk it out. Grab a friend or colleague and try to explain your argument out loud. The simple act of verbalizing your thoughts can often break the logjam and clarify your thinking.

The goal is to keep moving forward, even if it’s on a different part of the paper.

At maxijournal.com, we publish insightful articles across a wide range of fields, from science and technology to arts and education. Explore our curated content or learn how to contribute your own work.